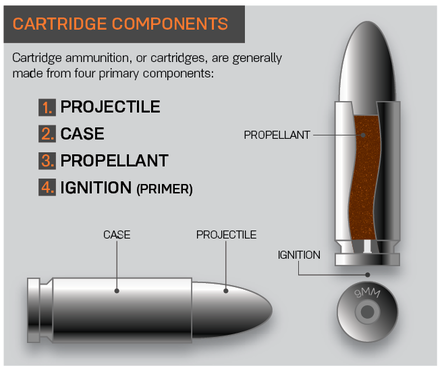

Ammunition can be used to describe a wide array of items, from the huge shells and powder bags used to load WWII naval cannons, loose powder and lead balls for muskets, or modern cartridges. The scope of this blog post focuses on modern cartridges. The bullet from a cartridge is used to create the majority of the data we use to characterize cartridges, most notably caliber. Caliber generally refers to the diameter of the base of bullet measured edge to edge. It’s not an exact naming convention however. For example, most .38 Special rounds actually measure 0.357 inches in true diameter, and a “.45 caliber” bullet could be as small as .451 inches or as large as .455 inches depending on the origin. Once cartridges are sorted into calibers, the bullet type is used to further differentiate them. The two major types of bullets are based on their construction: all lead or jacketed lead. An all lead bullet is about as close to a musket ball as you can get with modern firearms; a shaped chunk of lead with no external material. Lead remains the most common bullet material on the market for now; however there are several companies that produce bullets made entirely from a copper alloy. Jacketed bullets enclose the lead portion of the projectile with metal “jacket” material, usually made from a copper based alloy. The two most common jacket types are the full metal jacket, or FMJ which encloses the majority of the bullet but leaves the lead base of the bullet exposed; and total metal jacket bullets which fully enclose the bullet, including the base. Jacketed bullets were invented to deal with the problem of excess lead deposits in the barrel caused by the higher velocities associated with the invention of smokeless gun powder. PROJECTILE. Bullets are further broken down in to groups based on projectile shape. The most common jacketed bullets are commonly referred to as “ball” or “FMJ” ammo. Full metal jacket ball ammo is a lead core bullet encased in the aforementioned jacket material with no exposed lead in the frontal area of the bullet. The analogous all lead bullet is referred to as a lead round nose; its shape is similar to the ball ammo but lacks the copper alloy jacket. The next most common projectile shape is the hollow-point. A hollow-point bullet has a cavity in the frontal section of the projectile; this cavity is designed to react with the soft tissue and cause the bullet’s impact area to expand to a diameter greater than the base of the bullet. Hollow-point bullets can be found in all lead projectiles; for many years the standard issue cartridge for the FBI was a .38 Special semi-wadcutter hollow-point bullet that weighed 158 grains. The lack of a jacket on the now famous “FBI load” meant that bullet would generally expand to a considerable diameter. The current industry standard for hollow-point bullets is the modern jacketed hollow-point. Unlike the standard ball ammo, a jacketed hollow-point (JHP) usually has the base of the bullet enclosed by the jacket and some exposed lead in either the hollow-point cavity or around the nose of the cavity. The jacket material helps the bullet retain more of its weight after it’s expanded, giving it better penetration. This is especially important in defensive handgun rounds, which are limited to the single wounding mechanism of crushing tissue as they pass through it. Even though ball and JHP are the two types of bullets most frequently found; there are plenty of other types out there as well. CASE. Metallic cases are usually characterized by their shape, the type of rim, and the material they’re made out of. The case of a metallic cartridge is usually made of brass; other common materials are aluminum and mild steel. A cases’ shape refers to the amount of taper in the case walls or whether or not the case has a bottleneck shape. Bottleneck cases start with a larger diameter than necessary to fit the bullet, and are then necked down to accept a smaller projectile than the internal diameter of the case. An example of this is the .357 Sig, which starts a .40 S&W case, and then the open end of the case is reduced to properly fit a 9mm bullet. Tapered cartridges have a very gradual amount of taper to them, but lack a bottleneck. Cases can be further differentiated by the type of rim. Cartridges designed for revolvers will generally feature a prominent rim around the base of the case; the rim is greater than the diameter of the case itself and sets on the cylinder face. When the ejection rod is pushed, the revolver’s star grabs the case rim and manually ejects them. Most pistol ammunition is either rimless or semi-rimmed. A rimless case has a groove at the base of the case designed to accept the extractor claw on pistols. The extractor claw slides into this groove during the normal action of the firearm and then during the cycle of action post firing uses the groove to begin the process of removing the spent casing from the chamber. IGNITION. The last differentiation between types of cartridges is their ignition type. There are two ways in which the propellant in a cartridge can be ignited – rimfire ignition or centerfire ignition. Centerfire cartridges use a replaceable primer cap that is inserted into a pocket in the base of case. The primer is struck by the firing pin, and ignites the propellant. Centerfire ignition is more reliable and positive than rimfire ignition, which is a part of why all serious self-defense handguns use centerfire ignition. Metallic cartridges haven’t changed much since the early 20th century. The 9mm Luger was introduced in 1902, and with the exception of hollow-point bullet technology hasn’t changed in over 100 years. But even with technology this stable, knowing what each component of your cartridges does will increase your knowledge when selecting rounds for self-defense or target practice. By Caleb Giddings. Full article originally published in the May 2013 issue of GunUp the Magazine.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

January 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed